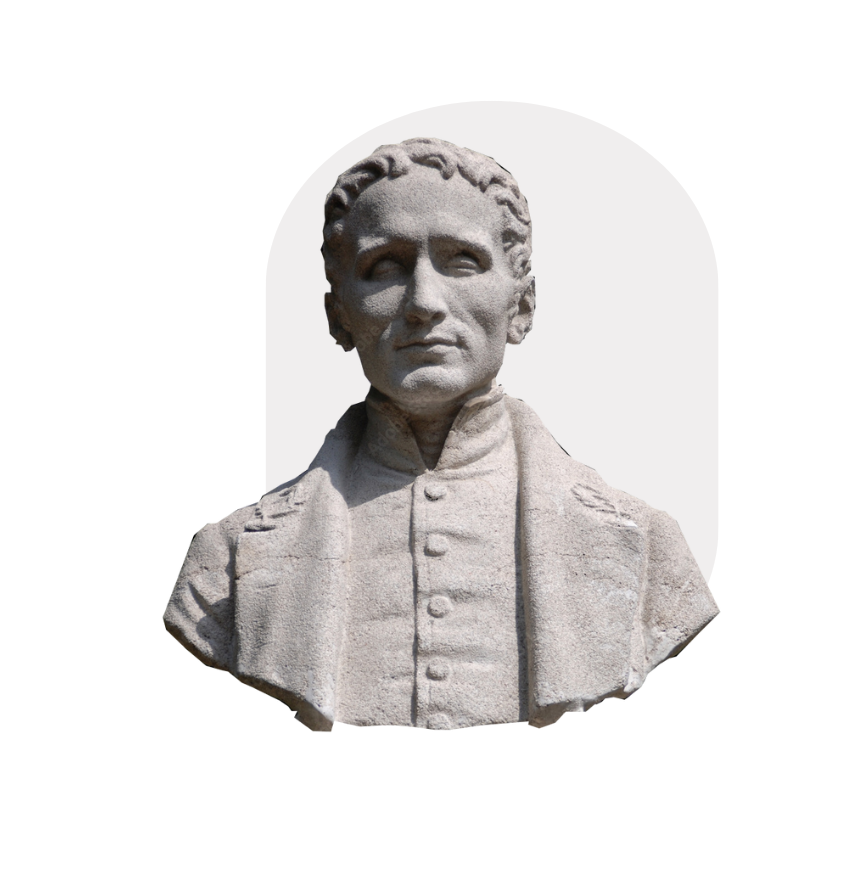

1809 – 1852

French educator who developed a system of printing and writing, called Braille, broadly used by the blind.

Louis Braille’s early childhood and education

Louis Braille was born in 1809 in the modest village of Coupvray, a short distance from Paris. According to Michael Mellor, he was already extremely frail from birth and was not baptised until three days after birth for fear that he would die. In the 19th century, the infant mortality rate was particularly high, even among the more affluent classes. But thanks to his mother’s devoted nursing, the young Louis Braille survived. Braille possessed a distinct comparative advantage in relation to certain other individuals who were blind. During his early childhood, while present in his father’s saddler workshop, Braille exhibited a strong desire to imitate his father’s work. In an attempt to mimic his father, he inadvertently grasped a leather strap and a billhook. Due to his lack of dexterity, the billhook accidentally hurt his eye, resulting in an immediate infection

Surprisingly, Coupvray had a doctor, a pharmacist, and a healer, which was rare for a small village such as this one. Each of them came to see young Braille, but their efforts were in vain as the infection grew worse and worse. He gradually began to lose sight in the one eye until he eventually lost it completely. It is unclear how the infection was transmitted to his second eye as well. He did not completely lose his sight until the age of five. Mellor suggests that the remedies and lotions applied by the healer may have aggravated his condition, as they often did. Furthermore, as Louis Braille was only a child, he must have done what every child would have done and rub his eyes, preventing it from healing. At the time, however, treatment methods for eye infections were not very advanced.

Braille’s parents, Simon-René and Monique, were both able to read and write, which enabled Louis to learn the alphabet very quickly. He learned it with the help of a wooden board, into which his father had probably driven nails. In 1815, when Abbé Pillon, the parish priest who had baptised him, died, a new parish priest of the Church of Saint-Pierre (Church of Couvray) was appointed, the Abbé Jacques Palluy. Noticing that young Louis Braille showed brilliance and a desire to learn, he became interested in him and resolved to take him under his wing. As part of his education with Père Palluy, young Louis Braille was given lessons on religion and the various virtues of Christian life, such as empathy and compassion. These qualities, which he acquired in his early childhood, were indicative of the qualities he was to develop as an adult. He was a very devoted tutor to the success of his pupils and, more than that, to the deliverance of the sightless. Father Palluy and his parents soon understood that Braille had a tremendous thirst for knowledge and that his blindness would not prevent him from pursuing his education. Father Palluy had made a request to the new appointed teacher, Antoine Bécheret, who agreed to accept the child into his class. Everyday, he went to school accompanied by a boy who lived nearby. He was the only blind student in his class but also the most brilliant

Tuberculosis

Braille continued the rest of his education in Paris. But before entering the Institut des Jeunes Aveugles, Braille first passed through a religious institution. It was at this point that young Louis contracted tuberculosis. The streets of Paris were extremely unhealthy, and the rising waters of the Seine helped to spread the diseases. The blind in these institutes rarely went outside, and saw very little sunlight. The lack of staff meant that the blind couldn’t wash frequently enough. Additionally, the lack of proper medical care and treatment for tuberculosis during that time period would have made Louis’ illness even more challenging to manage. He likely experienced symptoms such as coughing, fatigue, and difficulty breathing, which would have made it difficult for him to focus on his studies and participate in daily activities.

The Braille Code

Despite these challenges, Louis persevered and continued to pursue his education, eventually developing the Braille system that revolutionised the way blind individuals read and write. His determination and resilience

in the face of adversity continue to inspire people around the world today.

Braille was lucky his parents could send to Paris; most parents living in rural areas could not afford it. Louis Braille’s time saw most blind people living in abject poverty, with only those with families supporting them able to afford it. They worked in rural areas as gardeners, fruit pickers, or peddlers, while those near towns were musicians, publicans, carillonneurs, water carriers, or circus performers. Many lived on the fringes of society, begging. Some blind beggars preferred this freedom, as they were accountable to no one. Despite learning a trade, some blind beggars returned to begging, refusing to take jobs in workshops.

Louis Braille gained valuable experience over a period of two years in acquiring the skill of reading the raised cursive type developed by Valentin Haüy. Together with his fellow students, Braille diligently studied Barbier’s method, and they were able to identify and discuss both its potential and its limitations. Pignier effectively maintained a certain distance from Barbier, to the extent that Barbier remained unaware of Braille’s method until 1833, a significant four years after Braille had already published his initial description of the six-point system (Braille, 1829). Braille’s system represented a notable advancement over Barbier’s initial concept, as it allowed for faster reading and could be adapted for various applications, including mathematics and music. “Braille”, named after its creator Louis Braille, is a tactile writing system that revolutionised communication for individuals with visual impairments. While it is often referred to as a language, it is more accurately described as a code. This distinction is important because Braille does not have its own vocabulary or grammar; instead, it represents the letters, numbers, and punctuation marks of various languages. The Braille code consists of a grid of six dots, arranged in two columns of three dots each. By combining different dot patterns, Braille can represent the entire alphabet, numbers, musical notation, and even mathematical symbols. Each character is represented by a unique combination of dots, allowing individuals to read and write using their sense of touch. The previous nocturnal system invented by Barbier consisted of a 12-dot system that was complex and difficult to learn.

For further reading

Bicknel, Lennard. (1988) Triumph over Darkness: The Life of Louis Braille. London.

Henri, Pierre. (1952) La vie et l’oeuvre de Louis Braille, inventeur de l’Alphabet des aveugles (1809-1852). Paris.

Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles. (1999) Louis Braille, 1809-1852: correspondance inédite, éditée à partir de lettres originales, archives INJA, Paris: INJA.

Liesen, Bruno. (2008) Six points de lumière enquête autour de Louis Braille. Bruxelles : Memogrames.

Mellor, Michael C. (2008) Louis Braille : le génie au bout des doigts, Paris: Éditions du Patrimoine.

Conférence sur Louis Braille par Farida Saïdi le 19 novembre 2013 à l’auditorium des Archives départementales de Seine-et-Marne. Louis Braille (1809-1852) | Archive départementales de Seine-et-Marne

Musée Louis Braille à Coupvray